Written by: Ian B.D. McIntosh, PhD, CxM, UW–Madison InterPro and ianTEACH LLC

The commissioning (Cx) Process has a rich history extending back to the early 1980s, where Walt Disney used it for the Epcot Center, the American Society of Heating, Refrigeration and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) convened its first Cx Guideline Committee, and the UW–Madison College of Engineering created its first Cx courses. Today, the Cx Process continues to provide a means of improving the performance of critical systems in buildings. However, there are nuances that must be addressed for it to deliver on promises that building owners have come to expect. This article explores an important nuance in commissioning that poses a dilemma in the industry by doing the following:

- Provide background definitions of building commissioning for those unfamiliar with the process.

- Summarize an otherwise complex commissioning process into just three key action items.

- Focus on one of these key action items to reveal a nuance that causes a dilemma.

- Suggest solutions to this dilemma.

Background and Definitions

What is the Cx Process?

The term “commissioning” has come under a lot of scrutiny over the years. Its origin dates to the early days of the shipbuilding industry, where sea vessels in the US Navy were “commissioned” to set sail with much pomp and prestige. Nautical traditions often included breaking a ceremonial bottle of champagne against the ship’s bow[1]. Therefore, the term has come to mean the starting up of something new and does not typically include aspects of its design and construction.

This is even true for our everyday non-technical parlance – for example, “the artist is commissioning a new mural for the community center to brighten up the neighborhood.” The main event conveyed here is the new mural to be painted, which did not exist before. One doesn’t necessarily think about the process of developing various design sketch options to select from a priori, the size, structure, and material for the mural to be painted on, and what kind of mood the local City Council is interested in to “brighten up the neighborhood.”

When we speak of the Cx Process in buildings, we define it per the formal guidelines of the ASHRAE. Specifically, ASHRAE Guideline 0-2019[2] states:

“The Commissioning Process (Cx) is a quality-focused process for enhancing the delivery of a project by achieving, validating, and documenting the performance of facility elements in meeting the objectives and criteria of the Owner. Cx extends through all phases of new or major renovation projects, from predesign to Owner occupancy, with tasks during each phase to ensure verification of design, construction, and operator training.”

Owner’s Project Requirements:

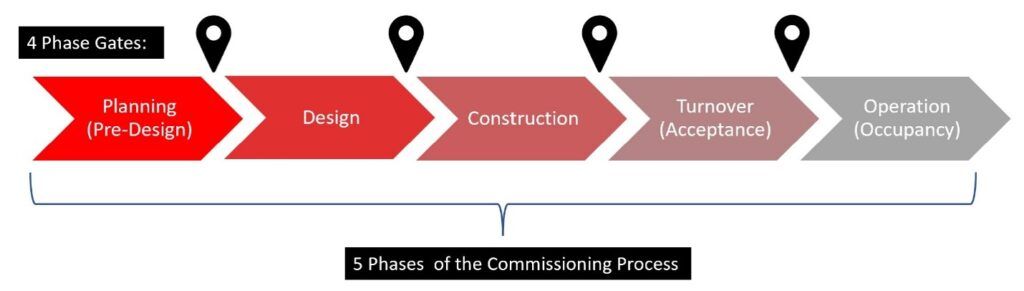

Clearly, this definition is very comprehensive and emphasizes a “quality process” as distinct from a one-time event, often dubbed Startup Cx in the building industry. With a careful read of the definition, one can observe the use of the very important phrase, “the objectives and criteria of the Owner.” This is also known as the Owner’s Project Requirements (OPR.) The OPR can also be expressed simply as “what the owner wants” to meet the needs of their facility. It is a formal document developed early during the pre-design phase of a project and needs to be continually updated to keep it current with decisions and changes made during all five phases of the project (see Figure 1).

Basis of Design:

In addition to the OPR, there is also another related document called the Basis of Design (BoD) developed and used during the Cx Process. The formal definition of the BoD per ASHRAE Guideline 0-2019 is:

“… a document that records the concepts, calculations, decisions, and product selections used to meet the OPR and to satisfy applicable regulatory requirements, standards, and guidelines. The document includes both narrative descriptions and lists of individual items that support the design process.”

While the OPR outlines “what the owner wants,” the BoD details “how to achieve it.”

What is the Cx Plan?

There’s at least one more significant document that is a vital cornerstone of the Cx Process and partners with the aforementioned duo to form an invaluable trio for Cx professionals to lead and manage the Cx Process. This document is called the Cx Plan, and is best thought of as “a roadmap for getting what the owner wants.” It presents several key details along the journey toward the destination of providing a quality building for the owner. These include:

- Cx project description

- A list of systems to be commissioned

- Description of Cx tasks

- Cx schedule of tasks

- Roles and responsibilities of the Cx Team

- Lines of communication

- Cx team contact information

- Copies of checklists

- Copies of test procedures

- Results of Cx tasks

Who is the CxA?

As with any process, success is heavily dependent on good leadership. For the Cx Process, the leader is known as the Cx Authority (CxA) and is responsible for shepherding the project through its various phases, verifying that the OPR is being met every step of the way. In situations where non-compliance is detected, a Cx issue is logged and tracked towards a timely resolution. Additionally, the CxA works closely with the Cx Team, which includes other project roles such as the Owner, Architect of Record (AoR), Engineer of Record (EoR), General Contractor (GC), subcontractors, operations personnel, and building users. Each bring their relevant expertise to contribute to the development of the OPR and the resolution of non-compliance issues.

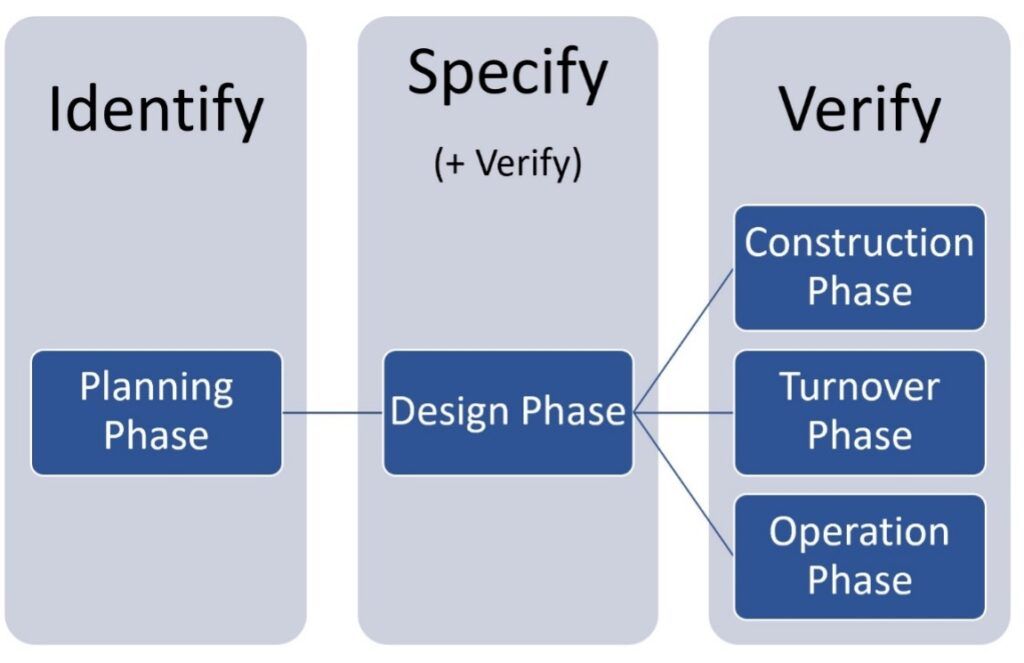

Identify, Specify, Verify

The Cx Process can be very complex with numerous Cx tasks and system types spanning all 5 phases of a project. This is especially true for more complex facilities like hospitals, laboratory buildings, and data centers. Thus, it is not uncommon for the Cx Process to last 2–3 years or longer for a full end-to-end ASHRAE Guideline 0–style commissioning. One useful approach to summarize the dozens of activities that a CxA will need to lead on a given project, is to consider them as falling into just three easy to remember actions – identify, specify, and verify.

- Identify – Start with the identification of the CxA for the project during the planning (pre-design) phase of the project. Once on board, they’re responsible for identifying, documenting (or aid in documenting) and maintaining the OPR, BoD, and Cx Plan.

- Specify – Develop legally binding drawings and construction specifications (i.e., construction documents) during the design phase of the project. These will convert the narrative-styled BoD into visual and constructible directives to the contractors to build the facility – literally from the ground up.

- Verify

- During the Design Phase – Compare the development of the drawings and specifications versus the OPR to verify compliance.

- During the Construction Phase – Compare the installation of systems, assemblies, and equipment versus the OPR, drawings, and specifications to verify compliance.

- During the Turnover Phase – Compare the performance of systems, assemblies, and equipment versus the OPR, drawings, and specification to verify compliance.

- During the Operation Phase – Compare first-year operations, personnel training, systems manuals, and warranties versus the OPR and project specifications to verify compliance.

Verification vs Inspection: What’s the Difference?

At this point, a note about the difference between the terms “verification” and “inspection’ is warranted. Is this a case of semantics? Aren’t they just synonyms? Grammatically, perhaps, but from a Cx Process perspective there’s a sharp distinction.

Verification is an objective process in which all quality requirements (i.e., OPR) are documented so that they can be measured. Verification determines if you are building a product in the correct way and all quality assurance (QA) and quality control (QC) activities are conducted properly.

Inspection is a physical act of measurement, non-destructive testing or gauging to assess conformance with specifications. Inspection is a technique that can be used within an overall process to prevent them – i.e., preventative. The Startup Cx described earlier is akin to inspection. The Cx Process is characterized by verification.

A Nuance of Verification

Addenda[3] [pronounced: uh-den-duh] – noun; plural of addendum – a list of things added

Errata [pronounced: ih-rat-uh] – noun; plural of erratum – a list of errors and their corrections

Commissioning verification has several challenging nuances. The following is a description of errata and addenda to standards in the construction industry, which can pose a dilemma for the CxA if they’re not aware or haven’t included sufficient scope/fees in their cost proposals to cover the gravity of verification responsibilities that may exist because of them.

A case in point is the COVID-19 global pandemic which has rocked the world in unprecedented and mammoth proportions. Various facets of the building design/construction industry have been affected in ways one would have never imagined. In the wake of the pandemic, many engineering professional organizations have improved their standards (via addenda) to help buildings respond more effectively in the event of similar emergency conditions in the future.

ASHRAE Standard 170-2021- Ventilation of Health Care Facilities[4] is a good example of this. Like many other standards, it is currently a part of a continuous maintenance program, which means that after a published edition, e.g., 2021 version of Standard 170, several proposals for changes can be made, reviewed, and approved by ASHRAE’s Standing Standards Project Committee (SSPC)[5]. To date, there are 15 Addenda[6], which have been proposed, reviewed, and approved. One of these, Addendum q, adds a new section 5.7 Emergency Conditions, which states the following:

“HVAC system design and arrangement shall address the applicable recommendations contained in the facility’s operational and emergency plan.”

Therefore, if a CxA is leading the Cx Process for a hospital building project and is involved in documenting the OPR and a specific, measurable, and verifiable OPR item explicitly refers compliance with Standard 170-2021, then it’s in the CxA’s (and owner’s) best interest to comb through Addendum q to assist in verifying compliance for the project. As stated earlier, the CxA works closely with other members of the Cx Team (in this case, the Engineer of Record) to identify what other addenda might be relevant to the verification of a particular OPR item.

Examples of relevant phrases throughout Addendum q which the CxA will find and have on their compliance “radar” include but are not limited to:

- “… Design features should be made clear in the final documents. All features should be completely commissioned for functionality.”

- “… Design documents clearly show the equipment, capabilities, and sequences for the pandemic mode. Anyone reviewing the design documentation, during construction and/or operation, can easily and readily see the pandemic mode feature and clearly understand how it is to be used.”

- “Design features for an emergency condition require compatibility with several principles, including… Be validated and/or functional performance tested.”

- “… The design team clarifies the necessary clean airflow that is required and in which rooms the clean airflow is required. The rooms and requirements are documented in a Basis of Design.”

- “… This documentation is included in the Basis of Design, on the plans and specification, in the facility operator’s training agenda…”

Similarly, Errata to Standard 170-2021[7] would have to be reviewed as well. This is because there might be typographical errors, misprints, misspellings, omission of approved material, or the erroneous inclusion of material that could impact the CxA’s verification task. An example of a meaningful error that would be good for the CxA to have on their compliance “radar” is the error of 1 air change and 2 air changes required per Table 7-1 of Standard 170-2021, instead of the corrected 2 air changes and 4 air changes required, respectively, for Minimum Outdoor ach and Minimum Total ach for inpatient spaces at Behavioral and Mental Health Facilities.

How to Verify OPR Compliance

Given the nuance described above, the following is a list of recommendations that may solve the dilemma of having to verify OPR compliance on projects:

- Know and stay abreast of the correct versions and editions of the formal documents that the OPR, BoD, construction documents reference for compliance. Recall that several professional standards (e.g., ASHRAE) undergo continuous maintenance and may have numerous changes represented in long lists of errata and addenda. The CxA should work closely with designers on the Cx Team to gain input on standards and the corresponding addenda/errata relevant to the OPR and BoD.

- Building owners should pursue edifying themselves about common verification nuances that their CxAs may have to deal with to properly verify compliance with their OPR. Thus, they can assign reasonable budgets that align with the level of rigor expected of the CxA.

- CxAs should include clearly and quantitatively written scope/fees (e.g., sampling rates) in their Cx cost proposals and discuss nuances of their verification work with building owners prior to beginning work.

- Periodically review the OPR, BoD, and construction documents to verify they’re updated and properly aligned with each other – i.e., there are no conflicting requirements among them.

- Use carefully crafted, updateable, and easy to use checklists during various phases (e.g., design, construction, and turnover) of the project to verify compliance with the OPR.

- Consider using commercial software to develop and use electronic checklists instead of paper-based ones that are harder to maintain and keep accurate.

- Checklists that are 100% completed by the design and construction team should be sampled (e.g., 10-20%) and double-checked by the CxA for accountability and OPR compliance.

Conclusion

The Cx Process can be summarized into three actionable steps: (1) identification of the OPR, the BoD and a Cx Plan; (2) specification of legally binding construction documents directing contractors what to build; and (3) verification for compliance by the CxA throughout the various project phases. Documenting project requirements with continuously maintained standards can have numerous addenda and errata creating challenges for the CxA to accurately verify compliance. There are several steps and measures one can take to address these challenges, and above all, staying up to date with standards and best practices will help ensure that your commissioning project complies with the OPR.

Next Steps

To learn more about the commissioning process and several techniques for verifying OPR compliance on your projects, visit our website to see a list of upcoming commissioning courses or reach out to Ian McIntosh.

Upcoming Building Commissioning Courses

References

[1] Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia. “Ceremonial ship launching.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ceremonial_ship_launching?form=MG0AV3. Accessed 16 Jan 2025.

[2] ASHRAE Bookstore In Partnership with Accuris. “Guideline 0-2019 –The Commissioning Process.” https://store.accuristech.com/ashrae/searches/50787392. Accessed 16 Jan 2025.

[3] Dictionary.com. https://www.dictionary.com. Accessed 16 Jan 2025.

[4] ASHRAE Bookstore In Partnership with Accuris. “ASHRAE 170-2021, Standard 170-2021 – Ventilation of Health Care Facilities (ANSI Approved; ASHE Co-sponsored)” https://store.accuristech.com/ashrae/standards/ashrae-170-2021?product_id=2212971. Accessed 17 Jan 2025.

[5] ASHRAE. “Search Results for: Continuous Maintenance”. https://www.ashrae.org/search?q=continuous%20maintenance. Accessed 17 Jan 2025.

[6] ASHRAE. “Standards Addenda”. https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/standards-and-guidelines/standards-addenda. Accessed 17 Jan 2025.

[7] ASHRAE. “Standards Errata”. https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/standards-and-guidelines/standards-errata. Accessed 17 Jan 2025.